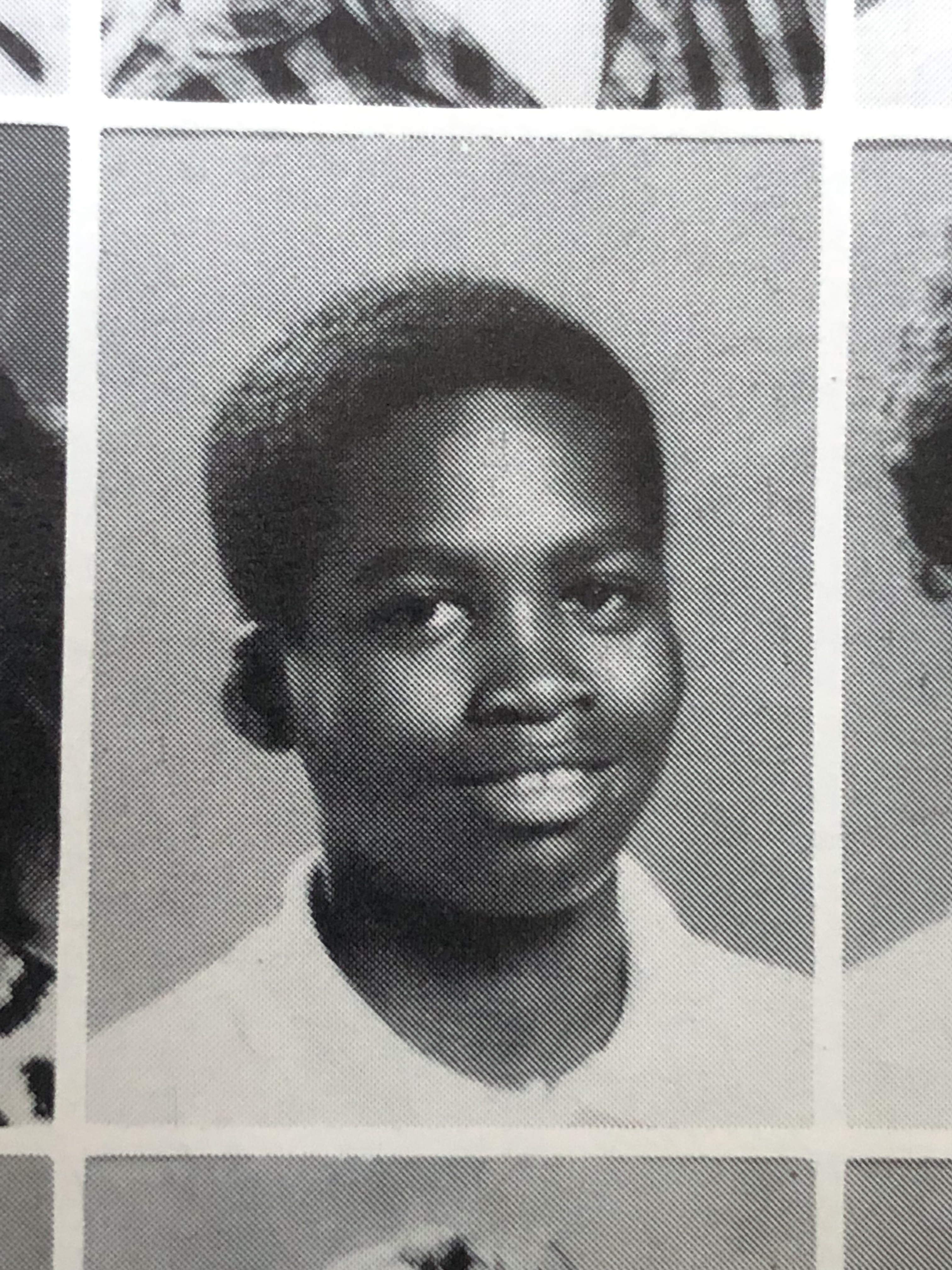

“For 900 days, I teleported through a portal and somehow managed to reinvent myself not knowing that the access was neither universal nor timeless.”

(excerpt of “900 days” from Forthcoming Book by Norman A. coulter jr.)

From 1984 to 1989 I commuted from 482 E. 48th Street and 700 E. 101st Street in South Los Angeles to Woodland Hills, Los Angeles, an upscale neighborhood against the Santa Monica Mountains. Woodland Hills serves as the threshold to more unapologetically wealthy cities like Calabasas and Agoura. At a glance, it boasts hiking-friendly topography and makes you reconsider the time you swore you would never sleep in a tent or “rough it” in the great outdoors. Every day was nothing short of a field trip for me as I left the undesirables save one…me. It was three hours roundtrip and what we poor Black folk would have called a “hellified” way to get an education paid for by California taxpayers like my mom.

In the 33 years since I stopped waking up before dawn to catch a city bus to a school bus which then drove me 34 miles to the promised land, I have only recently processed the significance of the 900 days I spent hunting down equity. The “e-word” gets a lot of publicity in the education sphere, namely the public because it distinguishes itself as an issue of access instead of one centered on uniform treatment and equality. Equity in education is supposed to be the augmentation that evens the playing field as if comparing education to a sports competition is even appropriate. When I arrived in Woodland Hills in the fall of 1984, I was ignorant of the voluntary integrative guise that euphemized failed Federal Legislation from the early 1970s. Back then, the United States government chose busing as the method to desegregate public schools from Boston, Massachusetts to Inglewood, California. And when it crashed and burned, what remained were voluntary one-way “privileges” for inner-city students. I benefited from the consolation prize of realization by my home state (California) that integration is an issue of conscience and not transportation. Mandated busing of students to the inner-city never stood a chance but the complexity of Brown vs. Board of Education revealed itself as racial disparity continued tracking along lines of social class.

I had heard the stories my mom told me of being part of the inaugural integrative efforts in Arkansas during the early-to-mid 1960s. She described how the teachers at White schools resented the audacious enforcement of Brown vs. Board of Education, infringing on the de facto segregation that was as Southern as hot water cornbread. The recalcitrance manifested itself through the mispronouncing of Black students’ names during roll call and purposeful emphasis of the word Nigger in texts that used the term. But during my elementary and junior high school years, the peculiar juxtaposition of a Crack Cocaine epidemic in the inner city along with meteoric rises in gang violence shrouded a confused Los Angeles Unified School District. There was no simple short-term solution to the one-way street of opportunity through public education. And whatever people thought about busing when they voted Proposition 1 down in 1979, LAUSD had to at least leave a conduit open to students like myself looking for more than the ‘hood could offer.

When Federal courts mandated desegregation, the unimaginable happened and White kids were forced to go to the other sides of the tracks to school. For all of the mythology associated with inner-city youth, their hyperbolized propensity for drug use, drug sale, fighting, and fatherlessness, the early 1970s literally threatened to transport White students into Hell. It was a rare moment in American history when privilege was revealed by proximity to its antonym. And it brought to bear the question, “What does integration really mean?” Is it when a poor Black male travels 34 miles for 900 days of his K-12 experience and is benevolently allowed to learn among rich Whites? Or does integration entail other intangible features like embracing fear because the unknown person learning next to you is a personified opportunity for growth? Is the end game of integration simply policy and forced mixing? Is integration a code word for sharing privilege with the hapless have-nots who are believed to have created their own plight? Or is it when empathy moves, say, the people of California to look so closely at the neighborhoods to which they would never send their own children for school that they exhaust themselves to right the ship for everyone. For 900 days, I teleported through a portal and somehow managed to reinvent myself not knowing that the access I had was neither universal nor timeless.